March 29, 2022:

Winner of GEM Outstanding Student Poster Award:

EPSS Space Physics graduate student Colin Wilkins won an award for best Inner Magnetosphere Section Poster at the 2022 Geospace Environment Modeling (GEM) Summer Workshop last week. Colin’s posted was titled “Statistical Characterization of the Electron Isotropy Boundary from ELFIN Observations.”

|

The GEM meeting is the premiere topical conference in Magnetospheric Physics; this year it attracted about 320 people, including more than 100 of them students from around the world. Colin’s was one of a handful selections, in the most competitive section. Congratulations!

March 29, 2022:

THEMIS-ELFIN observations of whistler wave electron precipitation :

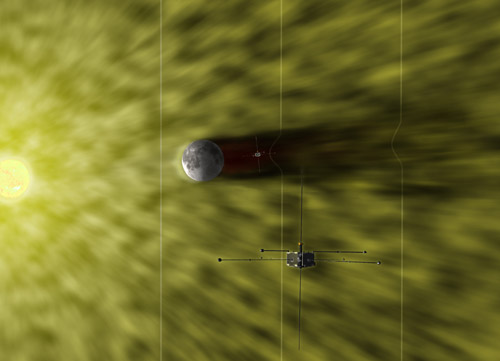

UCLA scientists have discovered a new source of super-fast, energetic electrons raining down on Earth’s atmosphere, a phenomenon that contributes to the colorful aurora borealis but also poses hazards to satellites, spacecraft and astronauts.

The researchers observed unexpected, rapid “electron precipitation” from low-Earth orbit using the ELFIN mission, a pair of tiny satellites built and operated on the UCLA campus by undergraduate and graduate students guided by a small team of staff mentors.

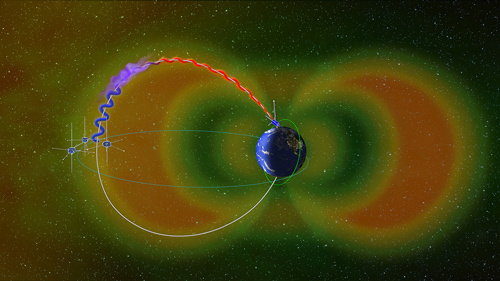

By combining the ELFIN data with more distant observations from NASA’s THEMIS spacecraft, the scientists determined that the sudden downpour was caused by whistler waves, a type of electromagnetic wave that ripples through plasma in space and affects electrons in the Earth’s magnetosphere, causing them to “spill over” into the atmosphere.

Their findings, published March 25 in the journal Nature Communications, demonstrate that whistler waves are responsible for far more electron rain than current theories and space weather models predict.

“ELFIN is the first satellite to measure these super-fast electrons,” said Xiaojia Zhang, lead author and a researcher in UCLA’s department of Earth, planetary and space sciences. “The mission is yielding new insights due to its unique vantage point in the chain of events that produces them.”

Central to that chain of events is the near-Earth space environment, which is filled with charged particles orbiting in giant rings around the planet, called Van Allen radiation belts. Electrons in these belts travel in Slinky-like spirals that literally bounce between the Earth’s north and south poles. Under certain conditions, whistler waves are generated within the radiation belts, energizing and speeding up the electrons. This effectively stretches out the electrons’ travel path so much that they fall out of the belts and precipitate into the atmosphere, creating the electron rain.

One can imagine the Van Allen belts as a large reservoir filled with water — or, in this case, electrons. As the reservoir fills, water periodically spirals down into a relief drain to keep the basin from overflowing. But when large waves occur in the reservoir, the sloshing water spills over the edge, faster and in greater volume than the relief drainage. ELFIN, which is downstream of both flows, is able to properly measure the contributions from each flow.

The low-altitude electron rain measurements by ELFIN, combined with the THEMIS observations of whistler waves in space and sophisticated computer modeling, allowed the team to understand in detail the process by which the waves cause rapid torrents of electrons to flow into the atmosphere.

The findings are particularly important because current theories and space weather models, while accounting for other sources of electrons entering the atmosphere, do not predict this extra whistler wave–induced electron flow, which can affect Earth’s atmospheric chemistry, pose risks to spacecraft and damage low-orbiting satellites.

Although space is commonly thought to be separate from our upper atmosphere, the two are inextricably linked. Understanding how they’re linked can benefit satellites and astronauts passing through the region, which are increasingly important for commerce, telecommunications and space tourism.

Since its inception in 2013, more than 300 UCLA students have worked on ELFIN (Electron Losses and Fields investigation), which is funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation. The two microsatellites, each about the size of a loaf of bread and weighing roughly 8 pounds, were launched into orbit in 2018, and since then have been observing the activity of energetic electrons and helping scientists to better understand the effect of magnetic storms in near-Earth space. The satellites are operated from the UCLA Mission Operations Center on campus.

“It’s so rewarding to have increased our knowledge of space science using data from the hardware we built ourselves,” said Colin Wilkins, a co-author of the current research who is the instrument lead on ELFIN and a space physics doctoral student in the department of Earth, planetary and space sciences.

Nature Comm. Editor’s Highlight

Nature Comm. Behind the Paper Blog Post

October 6, 2021:

Researchers Find Standing Waves at Edge of Earth’s Magnetic Bubble:

Congrats to Martin Archer et al. for their recent publication in Nature Communications. Using a combination of theory, THEMIS observations and global simulations, they discovered magnetopause standing waves propagating against the flow of the solar wind.

Earth sails the solar system in a ship of its own making: the magnetosphere, the magnetic field that envelops and protects our planet. The celestial sea we find ourselves in is filled with charged particles flowing from the Sun, known as the solar wind. Just as ocean waves follow the wind, scientists expected that waves traveling along the magnetosphere should ripple in the direction of the solar wind. But a new study reveals some waves do just the opposite.

|

| An animated illustration of magnetospheric waves, in light blue. At the front of the magnetosphere, these waves appear to be still. Credits: M. Archer/E. Masongsong/NASA |

Studying these magnetospheric waves, which transport energy, helps scientists understand the complicated ways that solar activity plays out in the space around Earth. Changing conditions in space driven by the Sun are known as space weather. That weather can impact our technology from communications satellites in orbit to power lines on the ground. “Understanding the boundaries of any system is a key problem,” said Martin Archer, a space physicist at Imperial College London who led the new study, published today in Nature Communications. “That’s how stuff gets in: energy, momentum, matter.”

Archer focuses on surface waves, meaning waves that require a boundary — in this case, the edge of the magnetosphere — to travel along. Previously, he and his colleagues established this boundary vibrates like a drum. When a strong burst of solar wind beats against the magnetosphere, waves race towards Earth’s magnetic poles and get reflected back.

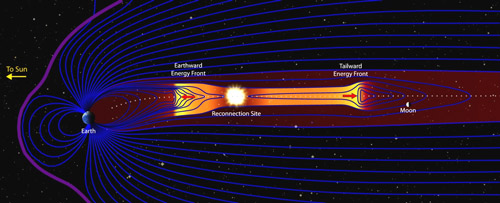

The latest work considers the waves that form across the entire surface of the magnetosphere, using a combination of models and observations from NASA’s THEMIS mission, Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms.

The researchers found when solar wind pulses strike, the waves that form not only race back and forth between Earth’s magnetic poles and the front of the magnetosphere, but also travel against the solar wind. Archer likened these two kinds of movement to crossing a river: A boat can go from one riverbank to the other (traveling towards the poles) and upstream (against the solar wind). At the front of the magnetosphere, these waves appear to stand still.

The THEMIS satellites’ observations from within the magnetosphere first hinted some waves might be traveling against the solar wind. The researchers used models to illustrate how the energy of the wind coming from the Sun and that of the waves going against it could cancel each other out. It’s similar to what happens if you try walking up a downwards escalator. “It’s going to look like you’re not moving at all, even though you’re putting in loads of effort,” Archer said.

| In this video, you can see and listen to standing waves at the edge of the magnetosphere. Data from the model has been translated into audio frequencies and stretched in time. The left panel shows a view looking down on Earth’s north pole. The right panel presents a view that slices through Earth’s magnetosphere, down the north and south poles. Red shows where the magnetic field grows stronger, while blue shows where it weakens. You first hear higher-frequency waves that are quickly replaced by a lower pitch — the standing waves that persist longer at the edge of the magnetosphere. Credits: Martin Archer/CCMC/NASA Download HD version from NASA SVS |

These standing waves can persist longer than those that travel with the solar wind. That means they’re around longer to accelerate particles in near-Earth space, leading to potential impacts in the radiation belts, aurora, or ionosphere. Archer expects standing waves may occur elsewhere in the universe, from the magnetospheres of other planets to the peripheries of black holes. Studying the waves close to home can help scientists understand such distant boundaries.

By translating the wave models and data into the audible range, we can listen to the sound of these curious waves.

September 24, 2021:

Earth can make auroras without solar activity:

Congrats to Xu Zhang et al. for their feature on Spaceweather.com! Using THEMIS observations and statistical analyses, they revealed an atmospheric electron beam source for ECH waves, which in turn can power the diffuse aurora.

|

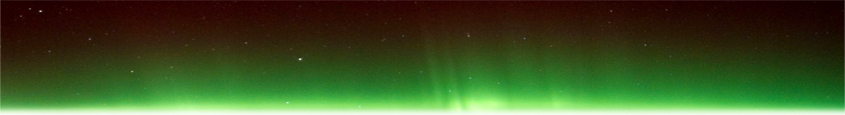

| Diffuse auroras and the Big Dipper, photographed by Emmanuel V. Masongsong in Fairbanks, AK |

No solar storms? No problem. Earth has learned to make its own auroras. New results from NASA’s THEMIS-ARTEMIS spacecraft show that a type of Northern Lights called “diffuse auroras” comes from our own planet–no solar storms required.

Diffuse auroras look a bit like pea soup. They spread across the sky in a dim green haze, sometimes rippling as if stirred by a spoon. They’re not as flamboyant as auroras caused by solar storms. Nevertheless, they are important because they represent a whopping 75% of the energy input into Earth’s upper atmosphere at night. Researchers have been struggling to understand them for decades.

“We believe we have found the source of these auroras,” says UCLA space physicist Xu Zhang, lead author of papers reporting the results in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics and Physics of Plasmas.

It is Earth itself.

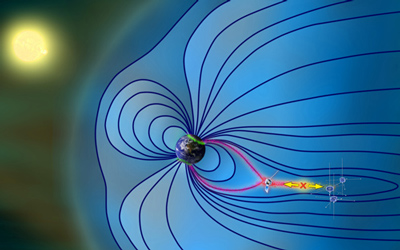

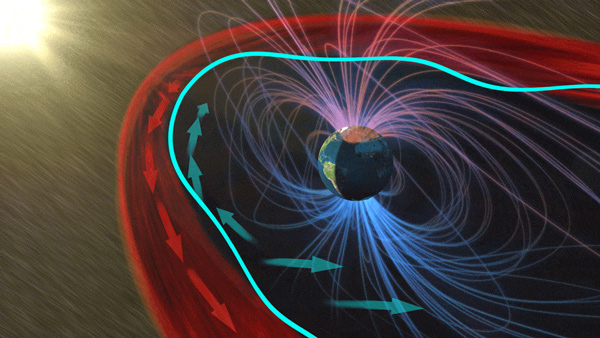

Earth performs this trick using electron beams. High above our planet’s poles, beams of negatively-charged particles shoot upward into space, accelerated by electric fields in Earth’s magnetosphere. Sounding rockets and satellites discovered the beams decades ago. It turns out, they can power the diffuse auroras.

The video, below, shows how it works. The beams travel in great arcs through the space near Earth. As they go, they excite ripples in the magnetosphere called Electron Cyclotron Harmonic (ECH) waves. Turn up the volume and listen to the waves recorded by THEMIS-ARTEMIS:

| THEMIS-E electric field wave burst mode (EFW) data converted to audio using real time and pitch, from nightside magnetosphere observations on June 1, 2011 16:06 UT. Low-energy electron beams (red) spray out of Earth’s north and south poles, converging in the equatorial magnetosphere (blue) to form Electron Cyclotron Harmonic waves (pink). The waves move Earthward, knocking other electrons (orange) out of orbit, which then fall back into the atmosphere to power the diffuse aurora (green). Video Credit, E. Masongsong UCLA EPSS, NASA Eyes Audio Credit, Martin O. Archer, Imperial College London, NASA HARP |

ECH waves, in turn, knock other electrons out of their orbits, forcing them to fall back down onto the atmosphere. This rain of secondary electrons powers the diffuse auroras.

“This is exciting,” says UCLA professor Vassilis Angelopoulos, a co-author of the papers and lead of the THEMIS-ARTEMIS mission. “We have found a totally new way that particle energy can be transferred from Earth’s own atmosphere out to the magnetosphere and back again, creating a giant feedback loop in space.”

According to Angelopoulos, Earth’s polar electron beams1 sometimes weaken but they never completely go away, not even during periods of low solar activity. This means Earth can make auroras without solar storms.

The sun is currently experiencing periods of quiet as young Solar Cycle 25 sputters to life. Pea soup, anyone?

Source: Phillips, T., Earth Can Make Auroras Without Solar Activity, Spaceweather.com, Sept. 30, 2021.

May 11, 2020:

SpaceNews.com interviews ELFIN about remotely operating CubeSats during Covid-19 Lockdown:

Students operating the twin Electron

Losses and Fields Investigation

(ELFIN) cubesats were heading

into finals at the University of

California, Los Angeles, when they realized they needed to quickly transition

to remote operations.

“As soon as all of us were done taking

three-hour tests, we had three-hour meetings to figure out what we needed the

satellites to do and how to make it as easy

as possible from a software and technical

perspective,” said Sharvani Jha, ELFIN

software development lead.

~

UCLA students began establishing remote access soon after ELFIN

launched in 2018 alongside NASA’s Ice,

Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2.

“We have winter break and summer

break where we would not be in Los Angeles physically,” said Rebecca Yap, ELFIN

mission operations manager. “Being able

to set up a flexible operations workflow

was important.”

Link to full article

April 17, 2020:

The journal Physics of Plasmas featured the work of Artemyev et al. as an Editor’s Highlight:

Mapping technique for nonlinear electron-wave interactions helps describe space plasma phenomena

Whistler-mode waves are circularly polarized electromagnetic waves generated by hot, anisotropic electrons. These waves are excited by the Earth’s radiation belts and accelerate electrons in various space plasma environments such as stellar wind and planetary magnetospheres. Inspired by a method used for simpler wave systems, Artemyev et al. developed a mapping technique to better understand the long-term electron dynamics in these phenomena as characterized by the nonlinear interaction of electromagnetic waves and electrons.

Whereas existing mapping techniques are limited to diffusive systems, the authors’ version is unique in that it can include nonlinear effects. By applying a Hamiltonian of electron motion with a finite wave-field perturbation, the technique considers two main processes – the long-term evolution produced by changes in electron energy caused by trapping, and by scattering.

Over time, particle trajectories in the map fill the entire available phase space, regardless of their initial energy distribution.

“Such stochastic dynamics is quite expected for diffusive resonance, but was unexpected for systems with nonlinear resonances,” said author Anton Artemyev. “This stochasticity means that long-term system dynamics can be modeled with the very powerful mapping technique.”

Looking forward, the authors plan to combine the developed mapping scheme with a realistic wave model – one that includes whistler-mode waves with significant variations in amplitude and phase coherence.

“Such combination would allow us to perform simulations of electron acceleration in radiation belts and compare these simulations with in situ spacecraft observations,” Artemyev said.

Source: https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/10.0001127

“Mapping for nonlinear electron interaction with whistler-mode waves,” by A. V. Artemyev, A. I. Neishtadt, and A. A. Vasiliev, Physics of Plasmas (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5144477.

January 13, 2020:

THEMIS observes nightside reconnection as power source of magnetic storm:

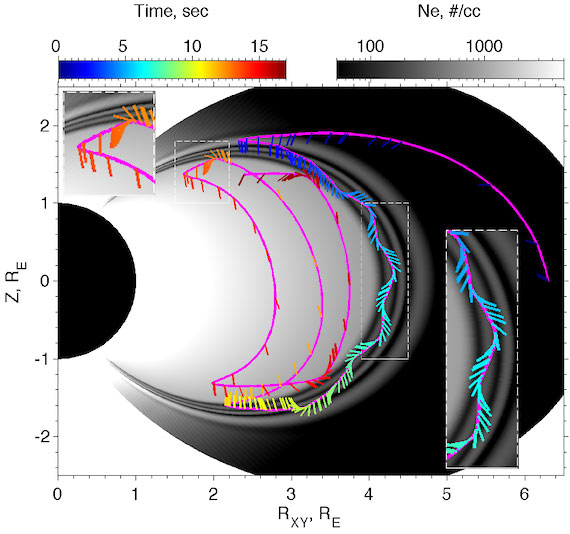

New THEMIS study finds that reconnection during storms can get much closer to Earth than previously thought, from where it can power storms directly. By feeding the ring current directly, this creates a qualitatively different mode of magnetospheric convection.

Magnetic storms originate closer to Earth than previously thought, threatening satellites

Beyond Earth’s atmosphere are swirling clouds of energized particles — ions and electrons — that emanate from the sun. This “solar wind” buffets the magnetosphere, the magnetic force field that surrounds Earth. In much the same way winds and storms create weather in our atmosphere, strong gusts of solar wind penetrating the magnetosphere can generate magnetic storms with powerful electric currents that can impact our lives.

A recent study in Nature Physics by Angelopoulos et al. shows that such storms can originate much that such storms can originate much closer to Earth than previously thought, overlapping with the orbits of critical weather, communications and GPS satellites.

|

| Brilliant aurora borealis captured over Yukon, Canada, during a geomagnetic storm. Its elusive driver, magnetic reconnection, was captured by a fleet of spacecraft near local midnight, with a large energy release surprisingly close to geosynchronous orbit. Credit: Joseph Bradley |

Magnetic storms can produce dazzling northern lights or hazardous particles careening toward spacecraft and astronauts, zapping them out of commission. Under certain conditions, magnetic storms can disable the electrical grid, disrupt radio communications and corrode pipelines, even creating extreme aurora visible close to the equator. “By studying the magnetosphere, we improve our chances of dealing with the greatest hazard to humanity venturing into space: storms powered by the sun,” Angelopoulos said.

An incident that illustrates the dramatic power of magnetic storms occurred in 1921, when such a storm disrupted telegraph communications and caused power outages that resulted in a New York City train station burning to the ground. And in 1972 the Apollo 16 and 17 astronauts narrowly missed what could have been a lethal solar eruption. These incidents underscore the potential dangers that should be assessed as more humans venture into orbit. If a similar storm occurred today, a separate study estimated, economic losses in the U.S. due to electrical blackouts only could surpass $40 billion a day.

How electric currents in space influence the aurora and magnetic storms has been long debated in the space physics community. Because the storms occur so rarely and satellite coverage is sparse, it has been difficult for researchers to detect the dynamic process that powers those storms. When solar wind magnetic energy is transferred into the magnetosphere, it builds up until it is converted into heat and particle acceleration through a process called magnetic reconnection. After decades of study, it is still unclear to researchers where exactly magnetic reconnection occurs during storms.

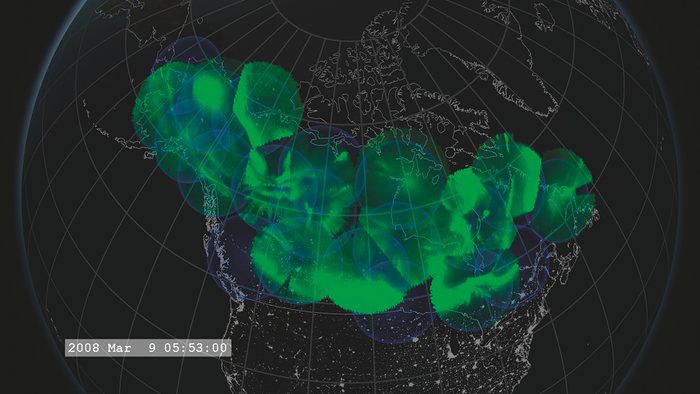

| Mosaic of THEMIS auroral all-sky cameras, imaging the night sky across Canada during the magnetic storm studied in the paper. Like a TV screen, the aurora reveals otherwise invisible particles and electrical currents arriving from space, causing the upper atmosphere to glow. Magnetic “footpoints” of orbiting THEMIS spacecraft (shown as blue, cyan and magenta squares, GOES weather satellite in yellow) correspond to their location in the magnetosphere, showing their close proximity to the storm’s origin. Moon light contamination shown using white arrows, blue line indicates midnight, magnetic local time. Credit: THEMIS ASI, Yukitoshi Nishimura, Boston University. |

Recent observations by multiple satellites have shown that magnetic storms can be initiated by magnetic reconnection much closer to Earth than previously thought possible. The three NASA THEMIS satellites observed magnetic reconnection only about three to four Earth diameters away. The researchers did not expect this could happen in the comparatively stable magnetic field configuration near Earth.Later, a weather satellite, which was nearer to Earth in geostationary orbit, detected energized particles associated with magnetic storms.

The weather satellite proved that this near-Earth reconnection stimulated ion and electron acceleration to high energies, posing a hazard to hundreds of satellites operating in this common orbit. Such particles can damage electronics and human DNA, increasing the risk of radiation poisoning and cancer for astronauts. Some particles can even enter the atmosphere and affect airline passengers.

“Only with such direct measurements of magnetic reconnection and its resulting energy flows could we convincingly prove such an unexpected mechanism of storm power generation,” said Angelopoulos, who is lead author of the paper. “Capturing this rare event, nearer to Earth than ever detected before, forces us to revise prior assumptions about the reconnection process.”

This discovery will ultimately help scientists refine predictive models of how the magnetosphere responds to solar wind, providing precious extra hours or even days to prepare satellites, astronauts and the energy grid for the next “big one” in space.

November 17, 2019:

Experimental Space Physics Researchers Honored by American Geophysical Union:

Congratulations to Anton Artemyev for winning this year’s American Geophysical Union’s prestigious Macelwane Medal. The medal is awarded yearly to 3-5 early career scientists across all fields of AGU for their depth and breadth of research, impact, creativity as well as service, outreach, and diversity. Anton has been at UCLA since 2015. He obtained his Ph.D. in 2012 from Moscow’s Space Research Institute. He is world renowned for his theoretical work on wave-particle interactions in space plasmas, incorporating non-linear effects into their description, with application at Earth’s radiation belts. He is also highly recognized for his contributions in the description and dynamics of plasma current sheets at Earth, Mars and Jupiter. He works closely with experimentalists and modelers, such that his elegant theories are grounded in reality. He was previously awarded the Zeldovich Medal (2014) from the Committee on Space Research and is Associate Editor of AGU journal: JGR Space Physics. His international reach is evidenced by strong collaborations with scientists and advising of students not only at UCLA but also at UCB, Italy, France and Russia.

Congratulations to Terry Liu (Ph.D. UCLA 2018, Advisor: Angelopoulos) for being this year’s recipient of the best thesis “Fred Scarf” award, in AGU’s Space Physics and Aeronomy Section. Terry’s thesis has revolutionized our understanding of how shocks in space and astrophysical plasmas operate and how they accelerate particles to high energies. Such acceleration is key to our understanding of space weather and the generation of cosmic rays. In eight highly cited AGU and Science Advances publications he showed how newly discovered phenomena called “foreshock transients” form, grow and evolve ahead of Earth’s own bow shock to create a highly dynamic setting where ions and electrons get accelerated. He used comprehensive, multi-spacecraft data analysis to develop powerful analytical models, which he then compared with computer simulations. His work has turned foreshock transients from an intellectual curiosity five years ago, to a required element of any modern-day plasma shock acceleration model. Terry is also a recent recipient of the prestigious NASA-sponsored Jack Eddy Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Congratulations to Terry Liu (Ph.D. UCLA 2018, Advisor: Angelopoulos) for being this year’s recipient of the best thesis “Fred Scarf” award, in AGU’s Space Physics and Aeronomy Section. Terry’s thesis has revolutionized our understanding of how shocks in space and astrophysical plasmas operate and how they accelerate particles to high energies. Such acceleration is key to our understanding of space weather and the generation of cosmic rays. In eight highly cited AGU and Science Advances publications he showed how newly discovered phenomena called “foreshock transients” form, grow and evolve ahead of Earth’s own bow shock to create a highly dynamic setting where ions and electrons get accelerated. He used comprehensive, multi-spacecraft data analysis to develop powerful analytical models, which he then compared with computer simulations. His work has turned foreshock transients from an intellectual curiosity five years ago, to a required element of any modern-day plasma shock acceleration model. Terry is also a recent recipient of the prestigious NASA-sponsored Jack Eddy Postdoctoral Fellowship.

October 22-24, 2019:

Space weather outreach at YOMO LA:

We were invited to the Youth Mobilization LA gigantic STEM outreach festival over 3 days at the LA Convention Center. All in all the event brought over 15,000 K-12 students, and you can see that space weather is hands-on fun for all agest! Most students had never heard of space physics or the magnetosphere, and now they are super interested in pursuing the subject after seeing ELFIN and hearing about our NASA missions. Click here for more photos.

October 6, 2019:

Space weather outreach at CicLAvia Street Festival:

EPSS was featured at the popular event CicLAvia on Oct. 6, 2019, where miles of downtown LA streets were closed off for ~10,000 cyclists to ride freely. UCLA’s Centennial celebration organized a huge exhibition in front of LA city hall for people to interact with UCLA history and present endeavors, and we were invited to present space weather and promote Exploring Your Universe with ELFIN, hands-on magnetic demonstrations, and a solar telescope for safe viewing of the sun. All booths were sustainably run by LADWP solar power. Thanks to our dedicated outreach volunteers, we reached well over a thousand people, many of them fellow Bruin alumni! Click here for more photos.

October 10, 2018:

Toluca Lake Elementary School visits:

We have established a fruitful partnership with Toluca Lake elementary, a Title 1 underserved school nearby. Fifth grade teacher Dennis Hagen-Smith is a UCLA alumnus (several in his family too) so he has invited us over many times to present space weather and ELFIN to his classes. Here is a photo of them visiting our labs at UCLA, and a newspaper article about our last visit to their school.

March 9, 2017:

UCLA EPSS novel aurora findings chosen for JGR cover art:

“UCLA EPSS research findings are featured on the February 2017 cover of the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. The study describes the properties of a newly discovered form of the northern lights, called throat aurora, on the dayside of Earth facing the sun (upward, out of frame). Using observations on the ground and in interplanetary space, the aurora are postulated to form through a novel combination of plasma flows inside and outside of the Earth’s magnetic field (the magnetosphere). Under certain conditions, solar wind interactions at the bow shock (~2 Earth widths upstream of the magnetosphere) can produce fast jets of hot plasma that perturb the outer boundary of the magnetosphere, as shown by previous UCLA EPSS studies. Sometimes cooler plasma “fingers” within Earth’s magnetosphere extend outward towards this boundary. The interaction of these two plasmas manifests as throat aurora, with radial spokes uniquely aligned along the north-south longitudinal axis.”

Source:

J. Geophysics Research – Space Physics, Volume 122, Issue 2, February 2017, Pages 1429–2733.

March 9, 2017:

ARTEMIS measurements of magnetic reconnection jets:

Every day, invisible magnetic explosions are happening around Earth, on the surface of the sun and across the universe. These explosions, known as magnetic reconnection, occur when magnetic field lines cross, releasing stored magnetic energy. Such explosions are a key way that clouds of charged particles — plasmas — are accelerated throughout the universe. In Earth’s magnetosphere — the giant magnetic bubble surrounding our planet — these magnetic reconnections can fling charged particles toward Earth, triggering auroras.

Magnetic reconnection, in addition to pushing around clouds of plasma, converts some magnetic energy into heat, which has an effect on just how much energy is left over to move the particles through space. A recent study used observations of magnetic reconnection from NASA’s ARTEMIS — Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence and Electrodynamics of the Moon’s Interaction with the Sun — to show that in the long tail of the nighttime magnetosphere, extending away from Earth and the sun, most of the energy is converted into heat. This means that the exhaust flows — the jets of particles released by reconnection — have less energy available to accelerate charged particles than previously thought.

When magnetic reconnection occurs between two clouds of plasma that have the same density, the exhaust flow is wildly unstable — flapping about like a garden hose with too much water pressure. However, the new results find that, in the event observed, if the plasmas have different densities, the exhaust is stable and will eject a constant, smooth jet. These differences in density are caused by the interplay of the solar wind — the constant stream of charged particles from the sun — and the interplanetary magnetic field that stretches across the solar system.

These new results are key to understanding how magnetic reconnection can send particles zooming toward Earth, where they can initiate auroras and cause space weather. Such information also provides fundamental information about what drives movement in space throughout the universe, far beyond the near-Earth space we can observe more easily.

The ARTEMIS spacecraft are working in tandem with other missions like Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms, and Magnetospheric Multiscale to form a complete picture of magnetic reconnection near Earth.

Sources:

January 17, 2017:

2016 Fall AGU Outstanding Student Paper Award Winner

EPSS graduate student Terry Liu has been awarded an outstanding student paper award at the 2016 Fall AGU meeting based on his presentation and paper titled “Observations of a new foreshock region upstream of a foreshock bubble’s shock.” Congratulations, Terry!

June 20, 2016:

THEMIS study featured on cover of GRL and received GEM Outstanding Student Poster Award:

UCLA PhD student Terry Z. Liu used THEMIS data from 2008 to profile the turbulent solar wind plasma upstream of the magnetosphere. Since the solar wind is moving at supersonic speeds, when it encounters the magnetopause, a collisionless shockwave forms. Some reflected ions can be energized to form a “foreshock bubble,” which Terry found can in turn form its own foreshock. The two THEMIS probes happened to be in just the right place and time to witness the bubble and the reflected ions in close succession, helping to reveal the complex geometry of the plasma interactions. Way to go Terry!

|

| A foreshock bubble’s shock, GRL Cover image. Credit: Emmanuel Masongsong and Heli Hietala, UCLA; NASA EYES. |

The image above is an artist’s representation of a baby foreshock emerging from its parent foreshock. Incoming solar wind ion beams (blue arrows) get reflected (spiral purple arrows) at Earth’s bow shock (red, far right). These reflected ions form Earth’s parent foreshock (faint orange glow) and gradually become diffuse (blurred spiral purple arrows). In this study, a solar wind discontinuity was observed by the THEMIS-B spacecraft (far left), causing some of the reflected foreshock ions to become trapped and thermalized (center, purple arrows bending to become yellow arrows in random directions). These hot ions expand and form a foreshock bubble with a hot core (yellow) and its own shock (red) due to fast expansion. The THEMIS-C spacecraft (center) observed that this new shock can also reflect solar wind ion beams (blue arrows) and form a baby foreshock (spiral purple arrows with orange glow).

For more specific details, please refer to the THEMIS Science Nugget Summary here.

February 25, 2016:

THEMIS featured in The Guardian, for new popular book on the aurora:

Featured in The Guardian: author and plasma physicist Dr. Melanie Windridge intertwines the cultural and scientific history of the aurora, and shares THEMIS mission breakthroughs in her new book, “Aurora: In Search of the Northern Lights.” Dr. Windridge reveals the rich history and enduring mysteries of the northern lights, from the ancient folklore of Arctic peoples to her own polar research adventures, elaborating on the latest findings about space weather and the complex mechanisms of the aurora. She also discusses the story behind the THEMIS mission, and the groundbreaking science fostered by its expansive array of All-Sky Imagers and magnetometers across the northern hemisphere, which continue to help researchers piece together critical elements of the auroral puzzle.

|

| Credit: Harper Collins |

“Canada has a vast amount of land underneath the auroral oval, so imaging the northern lights is an important research activity. This composite image from several cameras looking directly upwards shows how a twisted band of aurora can stretch all across the American continent. But it’s not simply pretty. Our atmosphere is the screen where the drama of the magnetosphere plays out. By studying the aurora we can learn about the processes happening far out in space.” -M. Windridge

|

| Mosaic of the aurora from the THEMIS All-sky imagers. Credit: NASA GSFC/SVS |

Source:

The Northern Lights Illuminated – in Pictures, featured on theguardian.com

The book was published by Harper Collins, more details can be found on the author’s website.

January 15, 2015:

JGR Editor’s Highlight, ARTEMIS 3D Lunar Wake Observations:

Unlike the Earth, whose magnetic field deflects much of the incoming solar wind, the surface of the Moon absorbs most of the particles that the Sun sends its way. This creates a void behind the moon that gradually refills with plasma, forming a cone-shaped “lunar wake.” However, the processes that govern refilling remain unclear, although models suggest they probably include a mixture of kinetic effects and effects particular to the dynamics of electrically conducting fluids.

Univ. of Alaska’s Hui Zhang and UCLA colleagues now provide a detailed characterization of the lunar wake and its relationship to the direction and strength of the solar wind. The researchers used two years’ worth of data from the Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence, and Electrodynamics of the Moon’s Interaction with the Sun (ARTEMIS) mission to characterize many physical properties of the wake, including its magnetic properties, ion and electron densities, temperatures, pressures, and flow, while simultaneously monitoring the solar wind.

The scientists find that the lunar wake trails behind the Moon out to a distance at least 12 times its radius. The edges of the wake generate density waves that form disturbances that propagate both outward and inward like the wake of a boat. This process can mostly be explained by known principles about the flow of plasma. In contrast, they find that kinetic effects most likely explain the mid-wake maximum in ion and electron temperatures, which may result from high-energy particles refilling the wake faster than their low-energy counterparts.

Notably, the researchers find that the angle between the direction of the solar wind and the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field also influence the shape and character of the lunar wake, making it more ring-like for angles close to parallel and flatter for more perpendicular configurations. The scientists also find that the interplanetary magnetic field itself bulges toward the Moon inside the lunar wake, although they can’t yet identify the mechanism behind this observation.

Sources:

Wendel, J. (2014), Satellite data yields detailed picture of the lunar wake, Eos. Trans. AGU, in press.

Aug. 7, 2014:

ELFIN Cubesat Mission is Funded! Undergraduates to Build First Satellite at UCLA

The Electron Loss and Fields Investigation CubeSat, or ELFIN, is a tiny satellite the size of a loaf of bread that still packs the scientific punch of significantly larger, more expensive satellites. When launched, ELFIN will determine how solar wind particles and radiation behave in Earth’s environment, a topic of increasing concern because magnetic storms can wreak havoc on space infrastructure like GPS, communication and weather satellites, and even damage the electrical grid here on Earth.

From the beginning, ELFIN had only scant internal funding, and the outlook for completion was unclear.

In spite of this uncertainty, a team of several dozen intrepid undergraduate students took on the project as their own, collectively putting in thousands of hours as a labor of love, developing and testing the satellite’s subsystems with the hope that the project would someday be fully funded.

After three years of diligent work and patience, the tide finally turned in 2013 when the U.S. Air Force awarded the team a $110,000 grant to continue development and buy much-needed parts. Last February, the opportunity to achieve their goal became even more real for these space Bruins when NASA’s CubeSat Initiative and the Low-Cost Access to Space program guaranteed them a launch spot.

Finally on May 23, the team was awarded $1.2 million jointly from NASA and the National Science Foundation, ensuring enough funding to put the space-qualified hardware in orbit and to operate it for six months from the UCLA Mission Operations Center, to be located on campus.

A collaboration between the Aerospace Corporation and UCLA’s departments of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences; Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (MAE); and Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, ELFIN will not only benefit UCLA students, who will have the opportunity to work on a real-world space program, but will also resolve a critical space physics question.

“The ELFIN experience is unusual in comparison to an industry that typically deals with one-ton satellites that take up to 10 years to build by a veritable army of engineers,” Turner said. “This will be an invaluable, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for our students — a ride to space they will never forget!”

The satellite is tentatively scheduled for launch in late 2016 or early 2017 as a secondary payload (similar to carpooling), which greatly reduces the cost of reaching space. From its polar orbit approximately 370 miles overhead, ELFIN will determine how high-energy electrons in Earth’s radiation belt (located roughly 25,000 miles above the equator) are scattered out of their cyclical orbits by naturally occurring ultra-low-frequency electromagnetic waves.

These electrons are guided along Earth’s magnetic field (which resembles a bar magnet) and fall into the atmosphere above the north and south poles, where their energy is transformed into the dazzling lights of the auroras. By analyzing the speed and direction of the falling electrons, the team will be able to tell what types of waves scattered them from the heart of the radiation belts. A sensitive on-board magnetometer will also look for the signature of these waves to confirm the scattering theory. Understanding this “emptying” of the radiation belts will help scientists predict the effects of future space weather storms.

“We are fortunate to be at UCLA in an environment with extremely competent staff, researchers and faculty who care and take the time to work one-on-one with us,” said Chris Shaffer, a senior in MAE and ELFIN’s student project manager. “We are building a team of students and staff with the mentality that there is nothing that we can’t do. That teamwork will be the hallmark of our project’s success. A banner stating that “Failure is not an option’ has been hanging in our lab ever since we started.”

Sources:

Press Release – UCLA undergrads are first to build an entire satellite on campus

Daily Bruin – Forecast From Space: Satellite built by student team may help predict magnetic storms

May 1, 2014:

THEMIS research featured in Journal of Geophysics Research:

The recent paper by UCLA researcher Christine Gabrielse et al., “Statistical characteristics of particle injections throughout the equatorial magnetotail” was selected as an Editor’s Highlight by JGR, Space Physics.

![(a) AL index. (b) Energy flux. (c) Energy flux (line spectra). Note that the ESA instrument goes near background levels around 02:00, 03:00, and 06:30 UT, explaining the behavior of the fitted channel between the ESA and SST instruments (26 keV). To avoid incorrectly selecting an injection from the fitted channel, we required that the energy flux at 26 keV be higher than that at 31 keV for selection. (d) Percent change in energy flux per minute [((Δj/j)/Δt)˙100] for each individual energy channel. Colors represent energy channels and correlate with the colors in the line spectra. Three consecutive energy channels must have a (Δj/j)/Δt that rises above the horizontal line at 25% for an injection to be selected. (e) Magnetic field in GSM coordinates. Increasing dipolarization is observed as each dipolarized flux bundle comes in, causing flux pileup around 04:00 UT. (f) Velocity in GSM coordinates. Flow reversals may represent vortices in the incoming flow and/or rebound in the flux pileup region. (g) Electric field in GSM coordinates calculated from −V × B.](http://themis.igpp.ucla.edu/images/index.table/Gabrielse1.jpg) |

| Gabrielse et al., Figure 1: Seven electron injection events selected using specific criteria. Events 1 and 2: Dispersionless injections. Events 3–7: Dispersed injections. |

Understanding the behavior of charged particles in the magnetotail

When the Sun spews charged particles toward the Earth, they can enter the magnetosphere and become energized as they move closer to the Earth’s surface. These energetic particles can induce the bright colors of auroras, disrupt navigational satellites, and even distort terrestrial telecommunications.

Previous research has found that the energization and transport of these particles—a process known as “particle injection”—may be correlated with the emergence of narrow, fast-flowing channels of plasma within the magnetosphere that travel earthward after energy is released in the Earth’s magnetotail. Curious about how far out these particle injections can be detected in the magnetotail, and whether or not they are actually caused by these narrow, fast-flowing bursts of plasma, Gabrielse et al. studied data from NASA’s THEMIS mission, which observes large-scale space weather events beyond the orbits of geosynchronous satellites.

The authors found that energetic particle injections could, in fact, be seen approaching Earth well beyond the previously recorded distance of 6.6-12 Earth radii, even up to 30 Earth radii away and possible further. They also showed statistically that these particle injections are indeed related to the narrow channels of fast-flowing plasma, where particles are energized by the flow channels’ electric fields. Understanding how these particle injections behave at points within the radiation belts to distances greater than 30 Earth radii away will help scientists develop better forecasts of potentially damaging space weather events.

Sources:

JGR Editor’s Highlight: Understanding the behavior of charged particles in the magnetotail

Feb. 14, 2014:

THEMIS-ARTEMIS-ELFIN Bring Space Plasma to Local Elementary School

The THEMIS/ARTEMIS and ELFIN spacecraft teams spent their Valentine’s Day spreading the love for space science at the local Nora Sterry Elementary School. As part of the school’s Science, Literacy, and Math event (SLAM), outreach coordinator Emmanuel Masongsong and undergrads Kyle Colton and Stephen Sundin shared their awesome magnetism and space weather demonstrations, eliciting “oohs” and “aahs” from students ages 3-8 and their parents.

The young ones were delighted with live pictures of the sun, liquid magnetism (ferrofluid), a handheld “mini THEMIS” probe, and the recently constructed Planeterrella plasma generator. Kyle and Stephen showed some cool magnetic magic tricks (copper tube showing Lenz’s law and a homopolar motor showing Lorentz force) and demonstrated the basics of satellite communication with Morse code.

Click HERE to see video of the UCLA Planeterrella in action!

The Experimental Space Physics Group is seeking K-12 educators who would be interested in magnetism and space science presentations at their schools or in their classrooms. For more information or to request a presentation, please contact emasongsong@igpp.ucla.edu.

Jan. 22, 2014:

THEMIS-ARTEMIS-ELFIN meet NASA Director Charles Bolden

The extraordinary military airman, astronaut, and chief NASA administrator Charles F. Bolden paid a visit to UCLA Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences on January 22nd, 2014. He gave an inspiring talk on his own journey through the space program and the current and future goals of NASA. He stressed the critical importance of science education in maintaining our nation’s leadership in all fields of technology, including space. Aside from the lecture, he met briefly with our undergrads and grad students to hear about the latest space weather research and cubesat development in our group, and then browsed our newly opened Meteorite Museum (the largest collection on the West coast). What an amazing individual with such varied accomplishments and honorable service. Thank you for visiting!

Dec. 3, 2013:

THEMIS and ARTEMIS a Magnetic Attraction at UCLA Public Outreach Event

The NASA THEMIS and ARTEMIS missions drew an impressive crowd at the 4th annual Exploring Your Universe outreach event, held at UCLA in Los Angeles, on Nov. 17, 2013. Representing two of UCLA’s active space missions, the exhibit exposed the public to “space weather,” the study of the sun’s activity and influence on Earth’s protective magnetic shield, the magnetosphere. Visitors were intrigued by informative posters and stunning videos on the electrical connection between our sun and the planets, and had the opportunity to question real space scientists and meet student researchers-in-training.

Kids and adults ages 7-70 enjoyed multiple interactive displays: touching glowing plasma spheres, seeing Earth’s and other planetary magnetic fields in 3D, comparing live pictures of the sun in different wavelengths of light, and even making their own sunspots! Although the wait in line was long, many lucky visitors witnessed the debut of a specially built display called the Planeterrella, an up-close demonstration of the solar wind and famed Northern Lights. This “aurora in a bottle” simulator was redesigned by Dr. Jean Lilensten at CNRS-IPAG in Grenoble, France, as a modernized version of the original Birkeland Terrella model built in the late 1800s to explain how the aurora are electrical in nature. The UCLA Planeterrella was especially popular because it helped visitors to actually see the sun-Earth connection in person, including solar flares, the solar wind, Van Allen radiation belts, and auroral ovals that can only be observed by satellites. It is the second educational plasma generator of its kind built in the US, after NASA’s Langley Space Center.

An estimated 1000+ space weather tourists dropped by the exhibit, asked awesome questions, and shared their knowledge about electricity and magnetism in space. Most visitors had already seen photos of solar storms, but they left with a greater appreciation of the solar wind and its electrified gases, as well as the importance of understanding their effects on Earth’s invisible magnetic field. “Space weather is important to study because, like weather on Earth, it is highly unpredictable and can damage critical GPS and communications satellites, harm astronauts on the space station, and worst case, cause extensive blackouts on the ground,” explained undergraduate engineering student Gautam Suri, who built the Planeterrella with graduate student Mac Booth.

By introducing the public to the sun-Earth connection and connecting the concepts of magnetism, electricity, and planetary science, visitors were able to grasp the importance of space weather and the satellite resources that help us predict solar and Earth-based “magnetic storms” that can threaten our modern technology. “We are fortunate to have a fleet of spacecraft observing potential hazards in near-Earth space,” said UCLA outreach educator Emmanuel Masongsong, “in particular the five THEMIS-ARTEMIS probes that continue to piece together the powerful electric and magnetic energy that fuels Earth’s radiation belts as well as the stunning auroral lights.” Most importantly, visitors young and old realized that magnets are not just cool toys or only for powering hybrid car motors and MRIs, they are a fundamental aspect of ongoing life on Earth and are key to the formation and evolution of planets, moons, and stars, extending far beyond our galaxy to other planetary systems throughout the universe!

Nov. 8, 2013:

THEMIS-MMS Conjunctions:

A Step Closer to Reality:

The recent maneuver campaign for the three THEMIS probes has been completed, and recent orbit determination has confirmed the maneuvers have been 100% successful. Between Sep. 25, 2013 and Oct. 22, 2013 we have executed a total of 19 maneuvers: There were 4 orbit change maneuvers, one attitude, and one spin rate adjustment per probe, and on September 24, we had our first ever collision avoidance maneuver for P3PD with a zero net change of the orbital period.

By lowering perigee and apogee altitudes we further increased our orbital drift. This final step in our preparation for the upcoming conjunctions with MMS in 2016 and 2017, originally planned for July, was delayed multiple times until early MMS thermal vacuum test results confirmed there are no major hurtles towards an MMS launch in late 2014. By doing so we traded as much as possible of our valuable drift time against the ability to account for a possible major launch delay of MMS into spring 2015 (which would have required imparting a drift in the reverse direction). Despite the recent MMS launch delay by one month there is still room for adjustments to preserve good quality lineups. We are therefore optimistic that we can still take full advantage of this very unique opportunity of THM-MMS conjunctions.

For the near term cooperation with the Van Allen Probes we increased the probe separation to about 7.5h. This nearly equal spread along the orbit was achieved through specific relative timing of the MMS-lineup maneuvers. And as you may have noticed, FS intervals have increased in duration to more typical 18-20hrs recently, thanks to the use of the White Sands antenna (thank you NASA).

All probes are in a clean spin rate window (low interference with FGM) and the attitudes have been optimized for the tail season in 2014 (sunward spin axis tilt) when we plan to return to smaller separations to obtain a second batch of 1-2Re inter-probe separation data. For the long term, THEMIS is on its way to be in the magnetotail during winter of 2016 and 2017 while again in conjunction with the GBOs! This will be an amazing opportunity to conduct Heliophysics System Observatory magnetotail studies.

Soon, there will be an update at SPDF, projecting the near and long term plans of THEMIS based on the post maneuver states. The current data at SPDF reflect the older long term plans based on only earlier maneuvers (from July), but will be updated soon. By having MMS orbits at SPDF as well, we plan to seek community feedback on how to best optimize the tetrahedral configuration of THEMIS around MMS.

We would like to use this opportunity to thank all of you who supported these maneuvers and in particular the flight dynamics, scheduling, and operation teams. We are confident that science will be well served with the outcome of all their hard work and that NASA will get the confirmation that their further support for THEMIS was worth their funding.

September 27, 2013:

ARTEMIS unravels energy conversion at reconnection fronts:

The twin ARTEMIS probes’ lunar vantage point was key to unraveling energy conversion in Earth’s magnetosphere, as reported in the recent journal Science. With an unprecedented alignment of 8 spacecraft including THEMIS, Geotail and GOES, researchers from UCLA, JAXA, and Austrian IWF observed reconection fronts moving towards Earth and away beyond the moon.

Solar storms — powerful eruptions of solar material and magnetic fields into interplanetary space — can cause what is known as “space weather” near Earth, resulting in hazards that range from interference with communications systems and GPS errors to extensive power blackouts and the complete failure of critical satellites.

New research published today increases our understanding of Earth’s space environment and how space weather develops.

Some of the energy emitted by the sun during solar storms is temporarily stored in Earth’s stretched and compressed magnetic field. Eventually, that solar energy is explosively released, powering Earth’s radiation belts and lighting up the polar skies with brilliant auroras. And while it is possible to observe solar storms from afar with cameras, the invisible process that unleashes the stored magnetic energy near Earth had defied observation for decades.

In the Sept. 27 issue of the journal Science, researchers from the UCLA College of Letters and Science, the Austrian Space Research Institute (IWF Graz) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) report that they finally have measured the release of this magnetic energy close up using an unprecedented alignment of six Earth-orbiting spacecraft and NASA’s first dual lunar orbiter mission, ARTEMIS.

Space weather begins to develop inside Earth’s magnetosphere, the giant magnetic bubble that shields the planet from the supersonic flow of magnetized gas emitted by the sun. During solar storms, some solar energy enters the magnetosphere, stretching the bubble out into a long, teardrop-shaped tail that extends more than a million miles into space.The stored magnetic energy is then released by a process called “magnetic reconnection.” This event can be detected only when fast flows of energized particles pass by a spacecraft positioned at exactly the right place at the right time. Luckily, this happened in 2008, when NASA’s five Earth-orbiting THEMIS satellites discovered that magnetic reconnection was the trigger for near-Earth substorms, the fundamental building blocks of space weather. However, there was still a piece of the space weather puzzle missing: There did not appear to be enough energy in the reconnection flows to account for the total amount of energy released for typical substorms.

In 2011, in an attempt to survey a wider area of the Earth’s magnetosphere, the THEMIS team repositioned two of its five spacecraft into lunar orbits, creating a new mission dubbed ARTEMIS after the Greek goddess of the hunt and the moon. From afar, these two spacecraft provided a unique global perspective of energy storage and release near Earth.

Similar to a pebble creating expanding ripples in a pond, magnetic reconnection generates expanding fronts of electricity, converting the stored magnetic energy into particle energy. Previous spacecraft observations could detect these energy-converting reconnection fronts for a split second as the fronts went by, but they could not assess the fronts’ global effects because data were collected at only a single point. By the summer of 2012, however, an alignment among THEMIS, ARTEMIS, the Japanese Space Agency’s Geotail satellite and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s GOES satellite was finally able to capture data accounting for the total amount of energy that drives space weather near Earth. During this event, reported in the current Science paper, a tremendous amount of energy was released.

The amount of power converted was comparable to the electric power generation from all power plants on Earth — and it went on for over 30 minutes. The amount of energy released was equivalent to a 7.1 Richter-scale earthquake. Trying to understand how gigantic explosions on the sun can have effects near Earth involves tracking energy from the original solar event all the way to Earth. It is like keeping tabs on a character in a play who undergoes many costume changes, researchers say, because the energy changes frequently along its journey: Magnetic energy causes solar eruptions that lead to flow energy as particles hurtle away, or to thermal energy as the particles heat up. Near Earth, that energy can go through all the various changes in form once again. Understanding the details of each step in the process is crucial for scientists to achieve their goal of someday predicting the onset and intensity of space weather.

Visualization of reconnection fronts, courtesy. J. Raeder/UNH

Sources:

UCLA Press Release – Lunar orbiters discover source of space weather near Earth

NASA Press Release – Several NASA Spacecraft Track Energy Through Space

Featured extensively in international media, including: Space.com, NBC News, Yahoo News, Science Magazine News, Science Daily, Phys.org, ScienceBlog.org, EurekAlert (AAAS), Environmental News Network, Red Orbit, Times of India, French Tribune, Le Scienze (Italy), and Newspoint Africa

Sept. 22, 2013:

Third radiation belt formation:

(Click here for animation of third belt)

Congratulations to Yuri Shprits and colleagues for explaining the mechanism of creation of the remnant belt, a 3rd radiation belt in Earth’s magnetosphere using a combination of THEMIS, Van Allen probes data and modeling. The results, which appear on the Sep. 22 (2013) issue of Nature Phys. go a long way towards revealing the separate physical processes that affect different electron belts, including wave scattering, and the effects of cold plasmaspheric plasma.

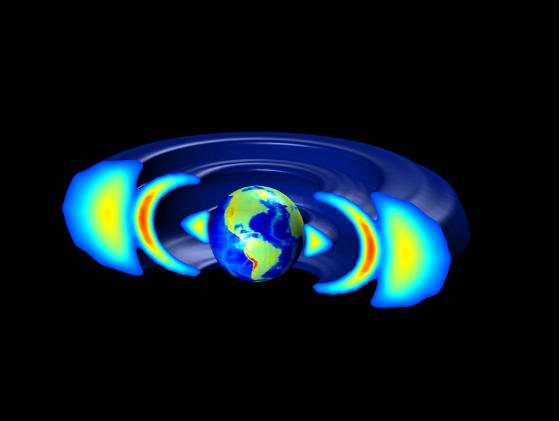

Since the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts in 1958, space scientists have believed these belts encircling the Earth consist of two doughnut-shaped rings of highly charged particles — an inner ring of high-energy electrons and energetic positive ions and an outer ring of high-energy electrons.

In February of this year, a team of Van Allen Probes scientists reported the surprising discovery of a previously unknown third radiation ring — a narrow one that briefly appeared between the inner and outer rings in September 2012 and persisted for a month (Baker et al., Science, Feb. 2013).

The above Van Allen Probe 2013 results confirmed earlier observations

by THEMIS researchers (Turner et al., Nature Physics, Jan. 2012), showing the rapid loss of outer belt electrons through the magnetopause, creating a distinct “remnant” belt. The remnant belt has a lifetime of hours to days for low energy (<2MeV) particles, that is dictated by the particle losses due to various plasma waves (hiss or electromagnetic ion cyclotron – EMIC – waves). However, an equatorial >2MeV population, was present in the Van Allen Probe 2013 study event for many weeks. The new modeling results by Shprits et al., show what causes the stability of the equatorial >2MeV electrons: it is the presence of the plasmasphere that protects these particles from EMIC waves, and the lack of resonance of these particles with hiss waves inside the plasmasphere.

“In the past, scientists thought that all the electrons in the radiation belts around the Earth obeyed the same physics,” said Yuri Shprits, a research geophysicist with the UCLA Department of Earth and Space Sciences. “We are finding now that radiation belts consist of different populations that are driven by very different physical processes.”

Source: http://newsroom.ucla.edu/portal/ucla/ucla-scientists-explain-the-formation-248209.aspx

Nature Physics: http://www.nature.com/nphys/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nphys2760.html

March 28, 2013:

THEMIS/ARTEMIS International Team Sees Auroras:

The Spring THEMIS-ARTEMIS Science Working Group meeting brought researchers together from all over the world to share the latest findings on the magnetosphere, solar wind, and the moon. Even better, attendees were rewarded with a substorm and brilliant auroras on the closing night! The truly diverse group of 50+ space and atmospheric physics scientists represented 7 countries and 24 different institutions, all coming together to share the latest findings in the near-Earth plasma environment. The meeting discussions were inspiring and productive, though the greatest thrill was during a visit to the Poker Flat Research Range just north of Fairbanks. Even after decades of studying space physics, this was the first opportunity for many to witness the auroras’ dazzling beauty in person.

At this state of the art facility, researchers stayed warm indoors (outside temp was -20F!) while patiently monitoring real-time solar wind measurements and ultra-sensitive CCD cameras displays. Periodically they would jump with excitement and a whir of outer garments as the early signs of a substorm appeared. Many were awestruck at their first sighting, and remarked on the surprising speed with which the green arcs consumed the sky. Many thanks to meeting organizer Dr. Hui Zhang and Dr. Don Hampton of University of Alaska for the Poker Flat tour, and to all attendees for their continuing contributions to THEMIS/ARTEMIS!!

(click thumbnails to enlarge)

February 19, 2013:

THEMIS 6th Year Anniversary (continued from home page):

Six Years in Space for THEMIS: Understanding the Magnetosphere Better Than Ever

Still going strong after 6 years in orbit, THEMIS continues to reveal the complexities of our magnetosphere in unprecedented detail. Read the official NASA 6th anniversary press release here:

NASA News: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/themis/news/six-years.html

Congrats to the THEMIS/ARTEMIS team and cheers to another year of exciting discoveries!

February 14, 2013:

THEMIS featured in AGU Geophysical Monograph:

A new AGU Monograph on auroral physics was recently published, prominently featuring THEMIS data. While in the past terrestrial and planetary auroras have been largely treated in separate books, Auroral Phenomenology and Magnetospheric Processes: Earth and Other Planets takes a holistic approach, treating the aurora as a fundamental process and discussing the phenomenology, physics, and relationship with the respective planetary magnetospheres in one volume. While there are some behaviors common in auroras of the different planets, there are also striking differences that test our basic understanding of auroral processes. The objective, upon which this monograph is focused, is to connect our knowledge of auroral morphology to the physical processes in the magnetosphere that power and structure discrete and diffuse auroras. The volume synthesizes five major areas: auroral phenomenology, aurora and ionospheric electrodynamics, discrete auroral acceleration, aurora and magnetospheric dynamics, and comparative planetary aurora. Covering the recent advances in observations, simulation, and theory, this book will serve a broad community of scientists, including graduate students, studying auroras at Mars, Earth, Saturn, and Jupiter.

A new AGU Monograph on auroral physics was recently published, prominently featuring THEMIS data. While in the past terrestrial and planetary auroras have been largely treated in separate books, Auroral Phenomenology and Magnetospheric Processes: Earth and Other Planets takes a holistic approach, treating the aurora as a fundamental process and discussing the phenomenology, physics, and relationship with the respective planetary magnetospheres in one volume. While there are some behaviors common in auroras of the different planets, there are also striking differences that test our basic understanding of auroral processes. The objective, upon which this monograph is focused, is to connect our knowledge of auroral morphology to the physical processes in the magnetosphere that power and structure discrete and diffuse auroras. The volume synthesizes five major areas: auroral phenomenology, aurora and ionospheric electrodynamics, discrete auroral acceleration, aurora and magnetospheric dynamics, and comparative planetary aurora. Covering the recent advances in observations, simulation, and theory, this book will serve a broad community of scientists, including graduate students, studying auroras at Mars, Earth, Saturn, and Jupiter.

Many spacecraft missions have probed the outer magnetosphere of Earth in conjunction with ground-based and space-borne imagers, and these have contributed enormously to our understanding of the coupled magnetotail-ionosphere system. It must also be said that the THEMIS project has given a new boost to the ongoing auroral investigations, and thus it is features prominently in this volume.

October 6, 2012:

THEMIS Research Highlight:

|

X-Y locations of the spacecraft observing the flow bursts for two data sets. Thick curve shows the GEO distance (6.6 Re). (a) Geotail locations in the events accompanied by GEO injections (red points) and in those without GEO injections (blue points). (b) Same as Figure 2a but for THEMIS spacecraft; events with simultaneous observations at two or three spacecraft are connected by line segments. Credit: V. Sergeev, St. Peterburg University

Congratulations to our colleague Victor Sergeev of St. Petersburg University! The editors of the Journal of Geophysical Research – Space Physics have selected his recent paper, entitled “Energetic particle injections to geostationary orbit: Relationship to flow bursts and magnetospheric state,” as a JGR Editor’s Highlight. It will also be featured as a “Research Spotlight” in Eos, AGU’s weekly newspaper, to be published soon.

Most high-energy particle injections do not reach geostationary orbit

The injection of high-energy particles into the inner magnetotail is often considered a reliable sign of a magnetic substorm. These injections are often thought to be caused by flow bursts, short-lived periods of narrow fast flow streams in the magnetotail. Analyzing records of flow bursts at the entry to the night-side inner magnetosphere, from 8 to 13 Earth radii, as seen by Geotail from 1995 to 2005, and by the Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions During Substorms (THEMIS) satellite from 2008 to 2009, Sergeev et al. (2012) found that most flow bursts do not cause the injection of high-energy particles to geostationary altitudes, and thus such injections are a poor measure of substorm activity. The authors identified 61 flow bursts using the Geotail records, and 44 using THEMIS observations. To determine whether an injection occurred with each of the flow bursts, they compared the Geotail records with publicly accessible pre-2008 particle injection data from Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) satellites, and turned to LANL scientists who had access to classified LANL satellite observations to confirm whether or not an injection occurred with each of the flow bursts in the THEMIS observations. The authors found that only 23 of the 61 Geotail bursts and 16 of the 44 THEMIS bursts were associated with the injection of high-energy particles into geostationary Earth orbit. The authors found that for a particle injection to make it to geostationary altitudes, the entropy parameter in the flow burst plasma needed to be comparable to the entropy at geostationary Earth orbit. The authors found that a strong solar wind driving, and high plasma pressure, at geostationary orbit could help drive up geostationary entropy and allow the injection of accelerated flow burst plasma.

September 19, 2012:

UCLA THEMIS Research Highlight:

The editors of the journal Geophysical Research Letters have selected Lunjin Chen’s recent paper, entitled “Modulation of plasmaspheric hiss intensity by thermal plasma density structure,” as both a GRL Editor’s Highlight and a feature in the “Research Spotlight” section on the back page of Eos, AGU’s weekly newspaper.

Plasmaspheric hiss amplification mechanisms identified (by Colin Schultz, from Eos)

A representative chorus ray that is guided by a density crest. The magenta line represents the ray path, along which wave normal directions are denoted by the short segments color-coded by the propagation time (up to 17 seconds). The model plasma density is shown in the background in gray scale.

Over the past 3 decades the hypothesis that chorus waves- a form of highintensity plasma wave often found in the outer magnetosphere- evolve into plasmaspheric hiss in the plasmasphere has grown in prominence. Plasmaspheric hiss is a form of low-frequency radio wave that is often observed in the regions within the plasmasphere that have high plasma densities. Plasmaspheric hiss is important in that the hiss waves interact with highenergy electrons in Earth’s geomagnetic field, carving out a swath between the inner and outer Van Allen radiation belts to form the “slot region,” a relative safe zone with minimized radiation hazard. Though modeled simulations of plasmaspheric hiss formation from chorus waves have been able to reproduce the major properties of observed hiss, they often underestimate hiss intensity by 10-20 decibels. Drawing on observations from the planet’s dayside made using NASA’s Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) satellite, Chen et al. examine two mechanisms that could make up for this shortfall.

June 26, 2012:

Jenni Kissinger’s paper highlighted by JGR and Eos:

The editors of the Journal of Geophysical Research – Space Physics have selected Jenni Kissinger’s recent paper, entitled “Diversion of plasma due to high pressure in the inner magnetosphere during steady magnetospheric convection,” as both a JGR Editor’s Highlight and a feature in the “Research Spotlight” section on the back page of Eos, AGU’s weekly newspaper.

Steady convection keeps Earth’s magnetic field in balance (by Colin Schultz, from Eos)

The onslaught of the solar wind on the Sun-facing side of Earth’s magnetic field causes terrestrial magnetic field lines to break through magnetic reconnection. The persistent pressure of the solar wind pulls the field lines and the associated plasma around to the magnetotail on Earth’s nightside, where magnetic reconnection occurs once again to form the plasma sheet region. This uneven distribution creates a pressure gradient that drives nightside plasma back toward the planet. The Earthward transport of this nightside magnetospheric plasma is known to occur in one of two ways: as a magnetic substorm or as steady magnetospheric convection (SMC). Substorms include acute inflows that cause plasma to pile up in the inner magnetosphere and have been tied to the onset of aurorae. SMC, on the other hand, has been proposed as a mechanism for rebalancing the plasma gradient established between the day and night sides of Earth’s magnetic field. Kissinger et al. compiled 14 years of magnetic field and plasma observations to study how plasma flows and magnetospheric conditions differ between SMC events and substorms.

May 3, 2012:

THEMIS/ARTEMIS UCLA Students Receive AGU Outstanding Student Paper Award:

Two of our graduate students, Michael Hartinger and Jennifer Kissinger, each received an Outstanding Student Paper Award for their presentations at the 2011 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco, CA. Congratulations to both of them on a job well done!

“Observations of a cavity mode outside the plasmasphere by THEMIS” by Michael Hartinger (abstract)

“Is a Substorm Expansion Required to Initiate a Steady Magnetospheric Convection Event?” by Jennifer Kissinger (abstract)

Magnetosphere simulation with THEMIS spacecraft conjuction in the equatorial plane. |

May 1, 2012:

THEMIS/ARTEMIS featured on Geophysical Research Letters Cover

A THEMIS/ARTEMIS mission spacecraft (P1) and Jimmy Raeder’s simulation rendition of a THEMIS major conjunction are prominently featured on the cover of today’s (March 16, 2012, Vol. 39, No. 5) issue of Geophysical Research Letters.This happened thanks to the review paper on substorm research by Victor Sergeev and colleagues which is published in this same issue.

Congratulations to Victor on his paper and to the THEMIS/ARTEMIS

communities for continuing the great pace of discoveries on substorms

and so many other topics spanning the entire magnetosphere (and which

are increasingly including the storms of the current solar cycle!).

Link to journal: http://www.agu.org/journals/gl/

Cover image: JPG – PDF

January 29, 2012:

THEMIS research published in Nature Physics Journal:

Congratulations to Drew Turner for his Nature Physics publication on: “Explaining sudden losses of outer radiation belt electrons during geomagnetic storms” published on-line on January 29 and making the news around the world!

Using combined data from THEMIS, GOES, and NOAA-POES satellites, Dr. Turner’s research explains how electron losses through the magnetopause resolve a long standing mystery of electron drop-outs during storm main phase.

Read the article here.

NASA press release here.